I think pretty much everyone has their own sort of definition of what "religion" is before they ever step foot into a RLG course at UofT. I know for a fact that I did, and it was quite a generalized idea that I followed with. To me, "religion" was generally centralized around the 'major' faiths that are practised in our world today - the Abrahmic religions, Hinduism and Buddhism were pretty much the only things I'd seen as a "religion". "Religion" was a very straightforward thing - there was belief in some sort of cosmic deity or being(s) to whom practitioners prayed to, as per requirements. There were some institutionalized rituals that were (expected to be) practised by adherents. Most of these faiths had some sort of sacred or religious texts that "told" them what it was they believed in and how they were expected to live out their lives. A very basic, and straightforward definition.

But it's really once I started taking courses under this program that I came to realize just how simplistic I was being with my understanding. There is just so much....more to it. And it surprised me to read just how much work had been put into this concept that I'd once found so simple - work that has been going for a number of years and from which numerous volumes of dedicated research and theories has been assembled. I never really did bother to consider the more "ancient" forms of belief that were in practise before the documented rising of the Abrahamic religions. The idea of magic, shamans, animism and various ancient superstitious beliefs being practised opened up a whole new way for me to understand and examine religion.

It's an age old question though - what exactly is religion? Clearly, the exposure to all these new ideas and belief systems marked my old definition as very limiting and therefore unusable. But it's a question that has been plaguing the scholarly field for decades. I think it's hard to really pin down on a suitable definition for what religion is, mainly because it's not necessary that all practises out there will have all the components that the definition calls for...and yet, they may have some of them. Is it possible to be considered a 'religion' if something only has a portion of the 'agreed upon' components? If not, what exactly would this belief system be considered, if not 'religion'? Various scholars have given their own definitions of religion and, as was expected, faults can be found in virtually all of them. Personally, I'm rather fond of Geertz's definition of religion that defines it as:

"A religion is a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic."

Despite the fact that I don't think it is a purely concise and full-proof one, I still prefer it over what else is out there - I suppose I'd call it the 'best' of what's at there at the moment. Still, I find that it captures a lot of the elements and general idea that I'd expect to see in a system organized around a particular set of beliefs. Of course, someone of a particular faith may not take so kindly to this definition - the idea that their beliefs are nothing more than a concept with an "aura of factuality" may be considered even insulting to some. Still, I think as a scholar of religion, we're not here to debate whether or not something of a religious nature is true or not true, we're just meant to be working with the facts and what we have. In that sense, I think this definition works quite well in that it's not focusing on a particular religious faith as being more 'true' than other...again, adherents to one probably wouldn't think the same.

What really sort of amused me was some of the terminology that was used to describe some of these older belief systems. The idea of an 'evolutionary model' of religion and references to beliefs of the past as 'primitive' and 'savage' seemed very arrogant on the part of the scholars who coined and used those terms. I just can't really buy the idea that the religious beliefs we have today are any more 'advanced' or 'civilized' compared to the 'savage' ones of the past.

I do agree with the idea of how beliefs from these early systems have, in some way, helped shaped some of the beliefs that are practised now - for example, going with animism and the idea that everything has an essence, or a 'soul' as it'd be referred to now. The idea of a "soul", or at least some sort of personal essence in human beings (and even in inanimate objects) is generally an important main concept in a number of religions. Not only does the "soul" appear in today's faiths, it's also the elements of myths and rituals that also come up as incredibly important to most current religions.

I don't necessarily agree with the idea that a society can be judged as 'advanced' based on its evolutionary level of a practised religious faith though. This just goes back to the idea of how I think it's unfair to label earlier practises as 'savage' when, in fairness, I don't really see much difference in how most of them would be even considered as 'backwards' to practises used today. They were different, yes - but I don't see how something like institutionalized worship found in Christian churches is more 'advanced' than ancient shamanic rituals. Both are just varying forms of practising beliefs and rituals - they are unique in their own manner, but no more or less than the other.

There's definitely a lot more to religion than I had originally thought. It is a far more complex thing than what I had considered it before. General worship and prayer is but a small portion of the elements that ultimately make up a religious belief - and even then, it's not necessary for these particular elements to be a part of it. That is the whole complex nature of defining what religion is. Again, while I do consider Geertz's definition to be the best of what's available, I'm still hesitant to say that it is a full-proof one. I think it'd be fairly difficult to really capture a definition that encompasses religions collectively in one phrase, without any sort of exceptions.

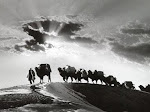

Honestly...something like this must be seen to actually be believed - a mere picture does it no justice. Still, it is interesting to think about how events from way back then, during the flourishing period of the Silk Road and the role it played in spreading religious beliefs far and wide are still holding a considerable deal of influence even today in modern times. I suppose it just goes to show that time does not matter and even the smallest of events can hold a key role in future events.

Honestly...something like this must be seen to actually be believed - a mere picture does it no justice. Still, it is interesting to think about how events from way back then, during the flourishing period of the Silk Road and the role it played in spreading religious beliefs far and wide are still holding a considerable deal of influence even today in modern times. I suppose it just goes to show that time does not matter and even the smallest of events can hold a key role in future events.